Origami : Art of Folding

Origami is the art of paper folding. An ancestral art, as delicate as it is economical, as simple as it is complex, it is appreciated by children and adults alike for the stimulation of imagination and creativity it brings. Originating from a long tradition, origami is above all a decorative art form for representing animals, geometric shapes and objects.

You don't need any tools to fold paper. This art requires nothing more than patience and dexterity, and knows no limits other than those of the imagination.

Origami's origins and history in Japan

Origami is thought to have been introduced into Japanese society after the invention of paper, which originated in China. The first papermaking techniques and paper products were imported to Japan by enterprising Buddhist monks who brought the technology back from China during the Heian period (794-1185).

The word "origami" comes from the Japanese verb "ORU" meaning to FOLD and the word "KAMI" meaning PAPER. The first origami creations were strictly reserved for religious purposes, due to the high cost of paper.

The earliest known origami pieces, according to written records, are a pair of folded butterflies, used to decorate wedding sake bottles. These butterflies, called "Ocho Mecho", date from the Heian period.

Modern Ocho Mechos decorating teapots

Not long after its introduction to Japan, origami spread rapidly and became a traditional cultural practice. The practice of paper folding, considered an elitist skill, was popularized by Heian nobles using "chiyogami" (千代紙 in Japanese) for gift wrapping. These chiyogami are made from sheets of "washi" paper (a name composed of the words "wa" (Japanese) and "shi" (paper) and referring to the traditional paper made from long pieces of Japanese mulberry bark). They are then stenciled or hand-printed with bright, colorful traditional Japanese floral imagery for a luxurious final result.

In the ancient Japanese imperial court, origami was both a refined and entertaining leisure activity.

Japanese paper craftsmen continued to improve the quality of washi paper for origami over time.

In 1680, a short poem by the poet and novelist Ihara Saikaku refers to butterfly origami, showing how paper folding was already rooted in Japanese culture at that time.

One of the earliest known instruction books on paper folding is "Sembazuru Orikata" (1797), by Akisato Rito, which shows how to fold bound cranes. These are folded from washi squares and interconnected.

Until the 19th century, although no longer reserved for lords and monks, origami was not the childhood artisanal art form we know today. It was mainly used for gift-giving and ceremonies. Since then, the art has been defined by various movements and trends.

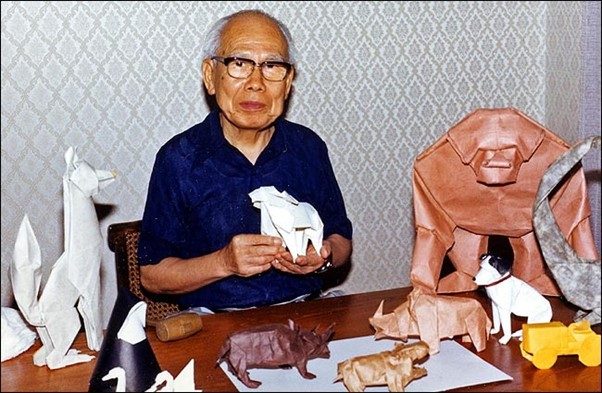

A Japanese artist, Akira Yoshizawa (1911-2005), had a particularly important effect on the evolution of origami as a sophisticated art form and highly cultivated contemporary practice. Yoshizawa-san is well known to origami enthusiasts for having created the practice of "wet-folding" (ウェット・フォールディングen). This technique facilitates the manipulation of folded paper by humidification, giving origami forms a sculpted rather than purely geometric appearance.

Artist Hoang Tien Quyet's surprisingly realistic and complex origami, source Melanie D. on Creapills.com

Akira Yoshizawa is also one of the creators of the Yoshizawa-Randlett diagram system, a revolutionary method of schematizing origami folding instructions. Yoshizawa-san's genius inspired a renaissance in the art of origami and played a major role in its international expansion through the standardization of models.

Origami's worldwide diffusion and expansion

Origami's influence on art and society has by no means been confined to the Japanese borders.

In the early 19th century, the German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel, who pioneered the first kindergartens, extolled the benefits of origami for children's development. A principle taken up years later by Italian educationalist Maria Montessori, who saw in the art of paper folding a formidable pedagogical tool.

Spanish author and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) also played an important role in popularizing origami. He was a famous paper-folder who could be found in cafés making paper birds. He wrote about paper folding in numerous works, including Amor y pedagogía (1902), and even used it as a metaphor for his deeper discussions of science, religion, philosophy and life.

Origami folding also spread to South America, mainly thanks to the work of Argentine physician and master folding artist Vicente Solórzano Sagredo (1883-1970), author of the most comprehensive paper-folding manuals in Spanish.

In England, Margaret Campbell published her landmark book Paper Toy Making in 1937, containing a vast collection of origami models. Two years later, British mathematician A.H. Stone's paper flexagons, whose paper structures curiously altered their faces when properly flexed, kick-started the popularity of paper folding, both recreationally and educationally.

For an example of a flexagon in action, see the following video:

After the Second World War, origami aroused growing interest in North America and became the subject of intensive research, notably by folklorist Gershon Legman in the USA. In 1955, Legman organized an exhibition in Amsterdam of origami by Japanese master Akira Yoshizawa, considered the greatest folding artist of his time, whose work inspired subsequent generations of folders.

Japanese origami master Akira Yoshizawa and his creations ; source : https://www.amusingplanet.com/2012/03/akira-yoshizawa-master-of-origami.html

In the 1950s, Lillian Oppenheimer was also instrumental in popularizing the word "origami" and bringing it to the attention of Americans. She founded the Origami Center of America in New York in 1958, used the relatively new medium of television to popularize the art form, and produced several books on origami with children's entertainer and TV star Shari Lewis. As Lillian Oppenheimer liked to say, "Why should the Japanese (alone) have all the fun?".

In the 1960s and early 1970s, American folders such as Fred Rohm and Neal Elias developed new techniques that enabled the production of models of unprecedented complexity.

In the late 1980s, Jun Maekawa, Fumiaki Kawahata, Issei Yoshino and Meguro Toshiyuki in Japan and Peter Engel, Robert Lang and John Montroll in the USA further advanced techniques, inspiring, for example, the folding of creatures and insects with multiple legs and antennae.

In the early 1990s, Robert Lang developed a computer program (TreeMaker) to facilitate the precise folding of bases, and another (ReferenceFinder) to find short, efficient folding sequences for any point or line within a unit square.

Origami and Architecture

Understanding origami's aesthetic beauty

Origami celebrates the importance of minimalism in art. Reflected by the term "shibumi" (渋味 in Japanese), which denotes a kind of understated beauty or simplicity, origami is often praised for its ability to transform a mundane object, the sheet of paper, into something beautiful.

The washi paper of which origami is made also reflects another element of Japanese aesthetics. Like life itself, paper is fragile and temporary, but origami artists attempt to harness it in a unique, tangible form in the hope of creating an object with a certain permanence.

Japanese origami craftsmen prefer to create representations of natural objects, such as flora and fauna, rather than non-living objects, more popular in other paper-folding cultures.

Today, contemporary artists who draw inspiration from Japan's rich aesthetic tradition are able to construct extraordinary origami, both dynamic and realistic, using this high-level form of artistic expression.

Origami-influenced architectural styles

The Japanese art of origami has had an impact on the architecture and construction industries. Its modern, minimalist design allows architects to imagine original contemporary constructions to create modern, atypical places.

For some, this art form has become a subtle, minimalist graphic art of angles and reliefs, as seen on the Hearst Tower in New York, or on the Origami office building in the heart of Paris's Golden Triangle, in the "8ème arrondissement".

The Hearst Tower was the first skyscraper built in New York after the fall of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001.

The six-storey masonry base, designed in 1928 by architect Joseph Urban, has been preserved.

The 40-storey modern tower, built above the lower structure, was taken over by British architect Norman Foster's firm Foster + Partners.

Triangular shapes and folds are used to give movement to the building's edges. The result is a sense of both the building's appearance within the city and the city's appearance within the building.

Hearst Tower, New York

Roy Rochlin//Getty Images

Origami office building © Vincent Fillon, source : http://manuelle-gautrand.com/

The Origami office building is located in the heart of Paris's Golden Triangle, in the 8th arrondissement. The building, which dates back to the 1970s, was completely demolished, with the exception of the four basement parking levels, and rebuilt in 2006. HQE-certified, it was designed by architect Manuelle Gautrand according to a dual concept of transparency and minerality. Triangles and folds were used for the panels forming the translucent second skin in front of the glass wall, creating a soft, subdued interior ambience and enlivening the exterior façade.

For others, origami served as a source of inspiration in the geometry and arrangement of shapes, for a remarkable and distinguished rendering. Good examples are the Biomuseo in Panama City and the Salling Tower in Aarhus.

Photos © The Biomuseo and Victoria Murillo

The Biomuseo is the first building in Latin America designed by architect Frank Gehry, whose wife is Panamanian. This museum, with its offbeat, multicolored structures, aims to tell the story of Panama's natural history and the planet's evolution over the past centuries. Of particular note are the colorful folded roofs.

Salling Tower, Photos © Torben Eskerod.

Copenhagen-based studio Dorte Mandrup designed the Salling Tower as a "dramatic urban sculpture" intended as a focal point and meeting place for visitors to the port of the Danish city of Aarhus. It features two observation platforms, one facing the water, giving the volume an arrow-shaped profile, while the second is located at the top, 7.5 meters above the quay. The white, perforated steel structure is reminiscent of paper folding.

Finally, we have those for whom origami in architecture combines aesthetics, inspiration, functionality and mechanical strength. Origami creates a play of light and shadow on folded surfaces, highlighting complex shapes. Giving the structure a fragile appearance, this art creates a surprising contrast with the building's resistant character. Origami's folds link both traditional and very modern lines in the aesthetics of the building, making it possible to play on impressions of lightness and relief to attract the eye. This combination of tradition and modernity brings refinement and a sense of purity and natural harmony.

F- House and A-House by Kubota Architect Atelier

As Japanese architect Katsufumi Kubota explains in an interview, his architectural art is to combine contemporary building materials and the use of origami folding from European architects with a very light Japanese style.

"Japanese architecture lived with nature, man and architecture lived with nature, that's the basic principle of traditional Japanese architecture. Whereas modern architecture, in order to resist natural disasters, has become more rigid and heavier. The European style uses a lot of iron, concrete and steel. So, my idea is to use these contemporary materials while lightening my architecture."

Origami has not only inspired architects from a visual and aesthetic point of view, but they have also incorporated it into their designs as a means of creating innovative and inspiring structures.

In conclusion

From religious practice to artistic innovation, paper folding has become an aesthetic medium in its own right. In Japan and around the world, origami artists are increasingly attracting the attention of small, well-known gallery owners and private collectors, who commission pieces selling for thousands of dollars.

There's no doubt that contemporary origami masters will continue to create astonishingly original paper sculptures that transcend the typical examples of this humble art and take it into a realm far beyond child's play. With its ability to provide simple, creative fun for all, as well as a complex and profound medium for artists and designers, origami will continue to inspire people all over the world.

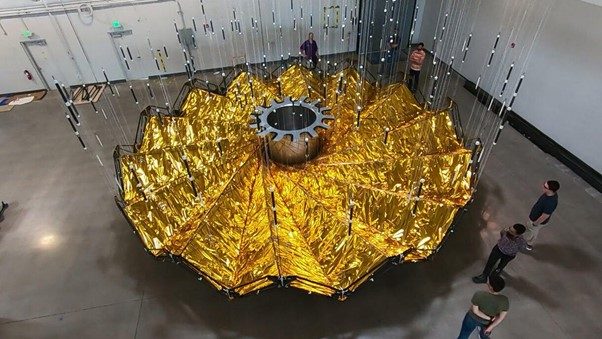

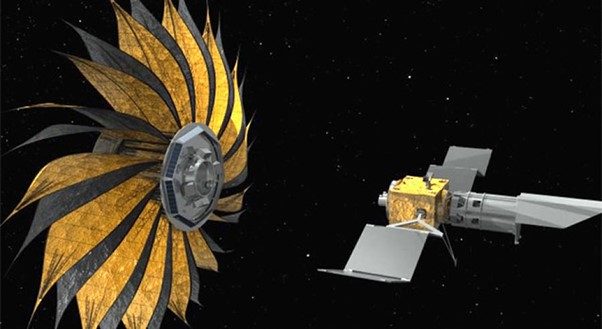

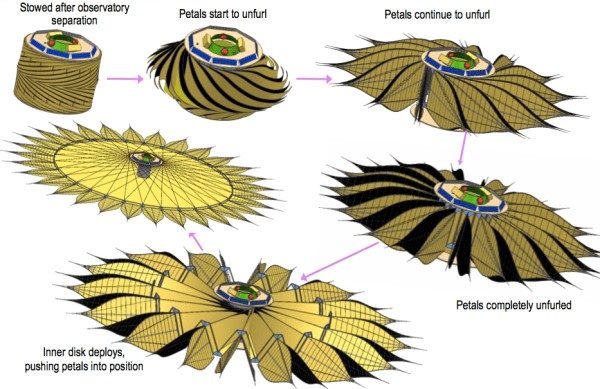

The "Starshade" project is an origami-folded disc that once deployed in space, flying far in front of a space telescope to block starlight, could help scientists get a clear view of space telescopes. The structure of the "star shield" is based on a "flasher" folding pattern, which enables it to roll up into a cylinder for launch. Once in space, this device then unfolds into a flat disk whose petals resemble those of a flower, as can be seen in the video and images below: